Many middle-class speculators with very little to lose were involved in the Railway Mania.

In the UK in 1847, pressures were high due to the government raising interest rates, resulting in a financial crisis and causing the railway share prices to crash. The Railway Mania didn’t cause this, but it made money market pressures worse. Many people paid for their shares in instalments and as calls were made for these payments, this money had to come from somewhere, increasing pressure on money markets.

According to John Eatwell, the Railway Mania was a 'prima facie example of a useful bubble' as investments with social value were left behind when the bubble burst.

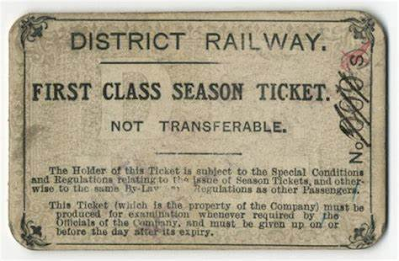

The national rail network that was developed as a result of the Mania was revolutionary. The reduction in time and costs of travelling made journeys possible, and more frequent and comfortable, for the middle and upper class.

According to Lardner, there were seven coaches a day operating between London and Edinburgh in 1835, and the trip took two days. By 1850, there were numerous trains operating daily, with a journey times of under 12 hours.

It's estimated that the social savings from railways were as much as 2% GDP by 1850 and 10% by 1900.

However, the means of authorising the railways and establishing a railway network was inefficient and resulted in a suboptimal rail network with unnecessary duplicate lines.

Studies showed that the 20,000 miles of rail which had emerged by 1914, 7000 miles of which were unnecessary. This inefficiency contributed to the poor performance of the railway companies.

A profitable railway could have been created if the government focused more on the efficiency of the rail network and less on regional interests,

Comments

Post a Comment